AS AN ADULT, NEWLY IDENTIFIED AS PDA, WITH PROBABLY AT LEAST TWO PDA CHILDREN.

Firstly, this is the first thing I have written on PDA and it will not be the last. Myself and my son are currently being assessed in regards to PDA and I am as certain as I can be of the outcome. One of my daughters also certainly shows traits of this. The below description of PDA is my own personal understanding of this neurotype from a year of researching through papers, videos, workshops and from my experiences of interacting with PDAers, my own experiences of life and my relationship with my son. It will differ from the standard current description because, if it didn’t, what would be the point of writing it.

What is PDA?

Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) is currently considered a distinct profile of autism, or an Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC).

It was originally called PDA Syndrome by Elizabeth Newson who observed a phenomenon in children suspected of having autism, whose difficulties, strengths and behaviours deviated from "classic" autism in some fundamental ways that were consistent with each other. She viewed it at the time as a separate condition (like ADHD) that had similarities to autism, but it has now been more widely recognised as a profile within the autism spectrum.

My views on this are complex and still forming. I will touch on this throughout this article but really that is a topic for another day.

What does the term Pathological Demand Avoidance actually mean?

Demand avoidance is simply avoiding doing things when they are considered a demand. Sounds simple. We all do it right? We don't want to do what we are told or do the stuff we find unpleasant! The first tricky bit of this is considering what is actually a demand. You may imagine it is when someone tells or asks you to do something. Actually demands are more widespread than this, constituting things that are asked of us, things that are expected or hoped of us, things that we expect of ourselves, including things that are just the normal expectations of society, like washing yourself.

Here is where the pathological bit comes in. People who are pathologically demand avoidant cannot do things when they perceive them as a demand. They avoid not only unpleasant tasks, but things they actually want to do, simply because they are told to, expected to, or the expectation of certain behaviour whilst doing it is too high. They avoid normal, everyday tasks like washing themselves, getting dressed, and going to bed. They avoid things that you wouldn't even see as a demand, because they demand them of themselves. PDAers can be paralysed by their expectations of what they believe they should be doing or achieving.

From the PDA society website:

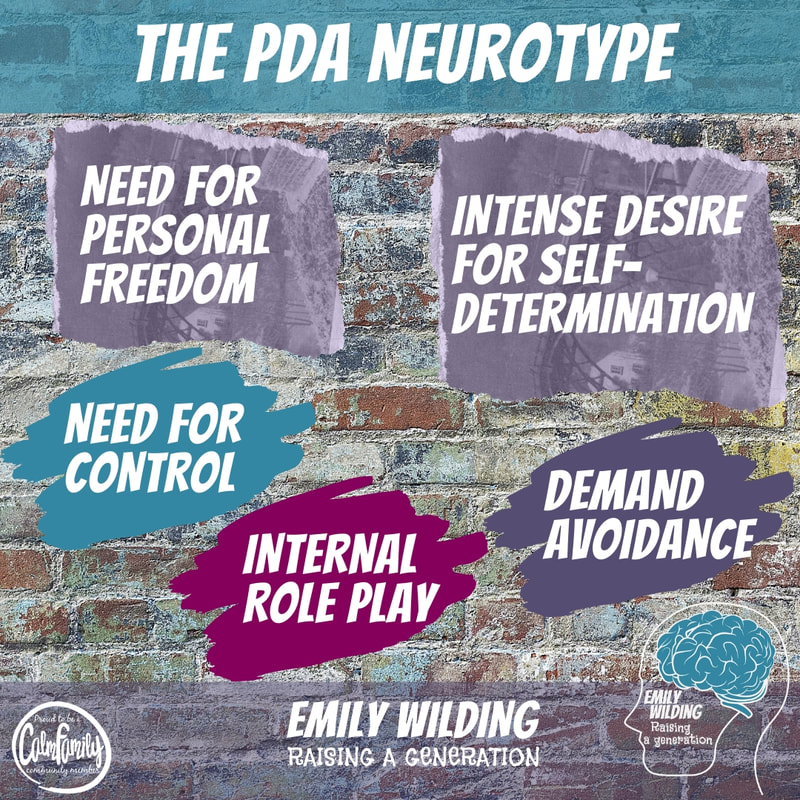

The Neurotype

The PDAer needs to live their life according to their own rules, their own code and compass, and would really prefer the world changed to fit that. This makes PDAers great activists and revolutionaries, people who lead and inspire others and ultimately pretty awesome people, except when they have to live under other people’s rules and demands.PDAers exhibit three main behaviours that stem from this intense need for freedom:

Need for control

I contend that the intense need for freedom is the fundamental neurology of the PDAer, and when this pervasive need is not met, or freedom is challenged, the consequent anxiety leads to a need for control, and the following two behaviours of PDAers. I want to thank several adult PDAers for helping me to understand this; it was enlightening for me personally. They are listed right at the bottom of the article.

Demand avoidance

The most obviously observed feature of the PDAer is, unsurprisingly, a person who will pathologically avoid demands from others and the demands of everyday life. The word "pathologically" is key here. It is the extreme and obsessive nature of the avoidance that implies there is a neurodivergent cause. This behaviour is again caused by their need for personal freedom being challenged. Autistic people who are not PDA display demand avoidant behaviour in certain situations, specifically when they are asked to do things that are uncomfortable for them as an Autistic person and therefore become anxious. This is not the same as the PDAer who will become anxious simply because a demand (even one for something they enjoy or wanted to do) is present.

Imagine if you will that a PDAer only has a certain capacity for demands in a day. The size of their capacity depends on how much demand has happened in the days and weeks before, how anxious they feel about other things and how much personal freedom they have been allowed recently. The demands of life take up some of this, so by the time they have washed and dressed, a PDAer with a small capacity might be done. The PDAer may choose not to do those things to give them capacity for things they would prefer to do. A PDAer can learn to regulate this capacity but must be allowed to do this freely, without suggestion.

The behaviours that PDAers will use to avoid demands can be equally extreme and pervasive and always include some social avoidance strategies. If a PDAer cannot avoid a demand, or the anxiety caused by the demands of life are too great, their anxiety will become too intense and they will end up in meltdown, which can be extremely serious for both the PDAer and the people around them. A PDAer who is in a general state of anxiety may skip very quickly though the stages or may immediately melt down at the slightest hint of demand.

|

Stage 1: Light avoidance

Distraction

Procrastination Negotiation Excusing themselves |

Stage 2: Strong avoidance

Retreating into fantasy or role play

Outrageous social behaviour Incapacitating themselves Making excuses that seem ridiculous |

|

Stage 3: Meltdown or shutdown

Self harm (physical and emotional)

Verbal or physical abuse of others Destruction of property Extreme exhaustion and inability to function |

Fantasy and role play

The third behaviour derived from the need for personal freedom is often down-played as simply “a possible feature of PDA that is potentially distinct from other autism profiles“. Role play and fantasy mind play is for me a key factor in this neurotype. PDAers are very comfortable (often obsessively) in role play or in their own personal fantasies (sometimes called day dreaming). I believe that as a direct result of the PDAer's need for personal freedom, they learn very quickly to retreat into their own personal worlds and characters that are entirely of their own making. This is something the PDAer has complete control over and complete freedom within. No external person has any control of this. If a PDAer chooses to role play with others, you will see them dominate the experience for the other person.

In Autistic people who do not have PDA, role play and fantasy may be something they struggle with, or they may enjoy much more formal role play as adults, entering effectively into another society that has definable rules that they understand and is potentially not as difficult to navigate as our society.

I believe this aspect to also be best described as pathological. This is because PDAers use role play in extreme ways in their everyday life. Here are the three most common ways that PDAers use role play to survive with their neurotype.

The PDAer will retreat into their own personal fantasies and role play in their mind to resist the demands of everyday life. They may also use a role or persona externally as a stage 1 social strategy to resist the demands of others. “No I am Elsa and Elsa doesn’t clear the table”.

PDAers will also retreat into a role or fantasy world to ease their anxiety and to try to make sense of social interactions they don't fully understand. This can restore balance and a sense of personal freedom.

PDA as part of the autism spectrum

Social communication and interaction differences

One of the reasons that this was thought to be a different condition than autism is that it was believed the the PDAer did not struggle with social communication and interaction at first. PDAers are often very social people, liking being around others and liked by people. PDAers are often charming, fun and exciting to be around, at least some of the time.

In more recent years it has been further observed that PDAers struggle with social communication but not in the same way as with other autistic profiles. Many professionals describe this as having “surface level sociability with a lack of deeper understanding” and although I can see how they came to this conclusion, I think this description may be misleading.

It appears to me that PDAers have, in most cases, a very astute understanding of human behaviour and a solid ability to understand what is happening for other people. I also believe that empathy usually scores very highly in the PDAer in much the same way as it does with ADHD, both in an emotional and a cognitive sense. However, it seems that the PDAer doesn’t always have the ability to put into practice complex social skills in a given moment. This means that, although surface level relationships and general social skills can be easy for the PDAer, especially if on their own terms, long-term relationships, or navigating complicated situations or dynamics, can be virtually impossible. I do not think this is through a lack of understanding.

PDAers appear to lack the ability to observe and respond to normal social boundaries due to having such a strong sense of themselves as deserving freedom. This makes a PDAer believe that they are, and should always be treated as, equal to everyone else. Whilst of course this is true and everyone should be, the rules of our society are quite different. There are common situations where one person, for example teachers, police officers and managers, are viewed as more important, wielding more power and influence. The PDAer will not only find any loss of control untenable, they will not understand why they are not able to freely challenge a person, regardless of their social status. They also won’t very much care, because these rules seem ridiculous.

In situations where there is a more socially equal footing, the PDAer may struggle socially because their need for freedom fundamentally overtakes their cognitive ability to read cues. The cues are there, and the PDAer might in reflection be able to read them, but in the moment,their freedom to speak, to give their opinion, voice their idea or take control is too strong. Afterwards there will potentially be shame at a mistake, and confusion because on reflection they may not be able to understand what happened due to being so caught up in their own free thinking.

This is one way that PDA is in some ways more similar to ADHD than ASD. People with ADHD struggle with social relationships, which is attributed to impulsive, hyperactive and inattentive communication, leaving people finding the ADHD person rude, thoughtless or uninterested.

Restrictive interests and repetitive behaviours

PDAers may display restricted areas of interest like Autistic people, and may even be less inclined than other Autistics to do and discuss things outside their field, due to this impinging on their personal freedom. Sometimes this might be less obvious in a PDAer due to the type of interests that they commonly pursue.

A PDAer’s area of interest is also more likely to relate to people in some way. Whilst other Autistic profiles tend towards intense interest in things like creatures, vehicles, objects and places, the PDAer is more likely to fixate on emergency service people, super-heroes, fantasy characters, and individual people, either in person or as celebrities. This is a generalisation of course, and the examples above are illustrative rather than exhaustive.

PDAers can become fixated on one particular person at a time, feeling a need to be with them, think about them, and talk about them constantly. They may need to know everything about them and feel unusually upset if the person spends any time with anyone else, even if this is completely reasonable. This obsession isn't necessarily romantic in nature, but a PDAer may mistake obsession for romantic feelings.

I have observed that, as well as commonly becoming fixated with particular people, adult PDAers have a greater tendency to be intensely interested in, and often study, human behaviour. This is commonly one of, or the, special interest of an adult PDAer. I believe that this stems from a high level of empathy, a need to “play roles” in order to cope with life, and a need to use social tools to avoid demands. PDAers accidentally study human behaviour in order to survive from a young age and so later in life, when they realise they actually understand humans pretty well, at least intellectually, they tend to want to learn more.

I have some interesting thoughts here regarding the similarities between the way the PDAers present “restricted interests” and the way ADHD people hyper-focus. I feel like this may require a whole article of its own but I would like to draw your attention to this as another potential example of how PDA seems to have much in common with both ADHD and ASD.

PDA and common neurodivergent traits

PDA Summary

As a quick summary, PDA is currently believed to be a specific form of autism that has at its core, an intense and pervasive need for personal freedom.

What you will see from a PDA person at any age is:

- Taking control over their own lives by not conforming to given rules and expectations (even if the judgement for this hurts them). Examples include changing their given name, gender, doing things backward etc.

- Taking or seeking control of the lives of others and any situation they can, though the intention is without malice, It usually comes from a place of trying to help the other party, or trying to be free.

- Avoidance of demands and expectations to an extreme and widespread degree. This may mean they cannot do very normal things of which they are physically capable, and will not comply, even if they want to.

- An appearance of lack of shame for extreme behaviour, though this is momentary and following an incident, shame will follow.

- Deriving great comfort in personal role play and fantasy, leading to an ability to mask their neurotype very effectively in certain situations.

- A desire to be sociable, with an ability to engage very well with others for a time

- Exhaustion following social interaction.

- Difficulty in perceiving and responding to social cues, even if they can see them.

- Difficulty with social boundaries.

- Difficulty in maintaining social relationships due to their need to be in control, their avoidance of demand and their struggles with social cues and boundaries.

- Repetitive behaviour displayed often as fixation with another person, or people.

- Difficulty regulating their mood and emotions, reacting strongly to perceived or minor stimuli.

- Huge amounts of anxiety if their personal freedom is not abundant, leading to very challenging experiences and behaviours.

As a child, a PDAer may have (but not necessarily):

- Been a passive baby, allowing things to be done for them more than others.

- Had some degree of language or communication delay but caught up quickly.

- Had difficulty maintaining friendships.

- Been “obsessed” with people (usually one specific person at a time).

- Seemed impulsive.

- Disliked or heavily questioned rules, the status quo and being told they cannot do things.

- Displayed potentially very difficult, seemingly oppositional and defiant behaviour

Thank you so much

Something I have observed in my son (diagnosed PDA) and wondered if it rings any bells of familiarity with yourself; A lot of his impusive behaviour and social difficulty, not to mention the demand avoidance, appear to me to occur because he is driven by instinct rather than conscious intention. It’s as if things he feels, focuses on, senses etc hit his sub-conscious hard and fast and completely bypass the rest of his mind, forcing a response on instinct before he gets a chance to think things through, so he has often reacted to a situation some time before he is even consciously aware of what he is reacting to. This was particularly obvious when he was a toddler, and the ‘brain catch up’ delay was longer – you could see the change in his eyes and face after he had reacted as the rest of his mind caught up and he attempted to puzzle out what he had just done and why. As he gets older the delay decreases and he is able to consider some things properly when calm and detatched, but when his emotions are engaged, even a little, he just can’t consider consequences in the moment (though he can describe some of them to you at other times) or stop himself/modulate or change his responses because he isn’t given the chance to. He lives by instinct and means the future isn’t just another country it’s a whole other universe for him. I have often wondered if this lies at the heart of his need for control/the demand avoidance. It must feel like someone else is controlling his own brain so much of the time that he has to grab and hold on to any type of control he can.

First off, thank you so much for your amazing thoughts and ideas presented here. Its put into words many of the thoughts I’ve struggled to express over the years.

It occurred to me recently that masking in school is another way of exerting control to protect personal freedom. It’s a way of protecting yourself from being admonished, criticised and publicly shamed, and provides an avenue to curry favour and gain more autonomy by way of reward. My 9yo daughter does it every day at school. She even did it as a tiny tot at her childminders. They used to say, we don’t think we’re seeing the real Kitty yet. If only everyone were so perceptive!

I do not have a PDA diagnosis but this article described me so exactly that I got freaked out and had to stop reading. Will finish later.

The freak out is mostly excitement/overwhelm at having possibly unlocked another piece of my neurology.

Thank you.

If you need any support or someone to talk it through with, please drop me an email/message. It was a huge lightbulb moment for me too and sometimes that feels uncomfortable as well as exciting.

I love this Emily. What a great overview 😁

I can’t thank you enough for writing this. I was diagnosed autistic in 2013 but I always felt a bit different to a lot of the experiences of autism, even female experiences, that I read. This is exactly me, apart from being oppositional at school as a child (I went off the scale in mid-late teens though). I realised I was probably PDA a few weeks ago but this has completely confirmed it for me and is the best thing I’ve read on PDA… and has created possibly the most revelationary moment I’ve ever had. Please carry on writing!

I too was not oppositional in school. My daughter is not either and I honestly believe that some presentations of PDA are much less oppositional, relying on being compliant as a coping technique in many situations, even thought it is impacting the PDAers mental health a great deal. I believe this people are actually in more danger in some ways, because they harm themselves rather than exploding outwards.

Thankyou. It helps to know that others have had similar experiences, rather than having to think maybe this can’t be me because of x, y or z.

I agree about internalising. I have self-harmed in the past. Also three years ago I was very ill with Conversion Disorder which the neurologist said was caused by repressed stress and anxiety.

I am starting to realise I have issues much deeper than I thought as I have been masking even to myself. Hopefully this can be the start of addressing that and moving towards something better.

Do you have any further information on the possibility of PDAers coping by being very compliant? It sounds a lot like me.

Also, do you have any information or advice on how to help in stage 3/panic attack when the PDAer gets aggressive or destructive?

This is the first thing I’ve ever read about PDA, and I’m reeling. I’ll have to read more, but I’ve been feeling a tickle in my brain for about a year, wondering about if I may have an ASD. I was diagnosed ADD (inattentive) about a year ago, and I’ve been actively reading/learning more about neurodiversity in that time. But something about the forms of autism/aspergers that I’ve read about, hasn’t felt right enough for me to seek a diagnosis. And of course, I wouldn’t seek a diagnosis unless I were already sure that the doctor would confirm my strong suspicion/KNOWING that this is ME.

Lord help me… lol

Well, I think this might be the one, so thanks and also SH#T!

I’ve often described to friends my “pathological need for control,” and I’ve destroyed romantic relationships over my complete inability to do chores, especially if that romantic partner had specific expectations about when, how or why they must be done.

Now I want to cry and laugh and tear my clothes off and go running off into the night 😂… BUT I WON’T, because I’ll remind myself that I’m cozy under the blankets, and it’s cold and wet outside, and it won’t be fun in reality, so I’ll be quite content with staying here and enjoying a vivid imagining of what that would look and feel like 🤣😭

Thanks for that super amazing and uncomfortable feeling that someone was peering directly into my brain and memories.

I think I’m a little bit in love 😉🤣 (but I’m sure you know how that is *sigh*)

Ok, well, now that I’ve acted in really socially awkward ways, let me quickly post this before remorse sets in and I’m too embarrassed to be real.

Thanks? I guess?? 🤣😭

I am sorry and also you are welcome? If you need any support at all, please drop me an email.

Thank you! I have only recently discovered this diagnosis (through parent support groups) and I am beginning to understand my 13 year old son much better. Nothing has ever really made sense before, and no one really seems to understand and it is exhausting as a parent trying to protect them from people who just make life harder. Thank you for the insight

I completely agree. It really hasn’t been that long for me either, just about a year. In investigating for my son, I discovered myself. For both of us, the PDA neurotype fits like a glove. The way our society works definitely makes life harder for our PDA children. Hopefully, with growing understanding, we can access better support.

This is a brilliantly articulate description of what I see in my son. I am also beginning to realise that it describes some of the struggles I have had in my life. Thank you so much. I will share this with my family and friends so that they get a better understanding.

Our children are our mirrors aren’t they. We learn so much of ourselves through them.